Salt

My Own Experience with Salt in my Diet.

When I was eating the standard diet that almost everybody has been eating these days, I had plenty of sodium in the likes of bread and processed foods that I was eating. However, when I went low carb, high fat and got rid of the processed foods and later when I quit plants altogether, I noticed that I was suffering more from night cramps in the legs etc. when I stretched. Clearly I was missing something.

My first experiment was with adding salt (sodium chloride) to my drinking water at a rate of 1 tsp to 1 litre of water. When I consumed somewhere between one and two teaspoons of salt a day the cramps disappeared.

Since then I've tried experimenting with upping the magnesium and potassium I ingest (in separate experiments) and found that neither of these did anything to stop cramps (in the absence of salt that is). I got up to 2 teaspoons of potassium bicarbonate in my daily diet and found that all it did was increase my average blood pressure from 120/80 to 130/80 in the month I was experimenting with potassium. Since it only caused a negative effect and there was no visible positive, I determined that my potassium intake was probably sufficient on my meat-only, plant-free diet.

I continue to use 1-2 teaspoons of plain table salt in carbonated, chilled water every day and if I don't accidentally drop below 1 teaspoon I have no recurrence of cramps. The bar staff at my golf course have a container of salt behind the bar and they all know to make my drink a plain 'sodium and soda' with a touch of ice.

When I was eating the standard diet that almost everybody has been eating these days, I had plenty of sodium in the likes of bread and processed foods that I was eating. However, when I went low carb, high fat and got rid of the processed foods and later when I quit plants altogether, I noticed that I was suffering more from night cramps in the legs etc. when I stretched. Clearly I was missing something.

My first experiment was with adding salt (sodium chloride) to my drinking water at a rate of 1 tsp to 1 litre of water. When I consumed somewhere between one and two teaspoons of salt a day the cramps disappeared.

Since then I've tried experimenting with upping the magnesium and potassium I ingest (in separate experiments) and found that neither of these did anything to stop cramps (in the absence of salt that is). I got up to 2 teaspoons of potassium bicarbonate in my daily diet and found that all it did was increase my average blood pressure from 120/80 to 130/80 in the month I was experimenting with potassium. Since it only caused a negative effect and there was no visible positive, I determined that my potassium intake was probably sufficient on my meat-only, plant-free diet.

I continue to use 1-2 teaspoons of plain table salt in carbonated, chilled water every day and if I don't accidentally drop below 1 teaspoon I have no recurrence of cramps. The bar staff at my golf course have a container of salt behind the bar and they all know to make my drink a plain 'sodium and soda' with a touch of ice.

Esmée La Fleur has written about the pros and cons of salt in the carnivore diet here

"As I stated at the beginning of this article, the issue of sodium is a bit complex. I have tried to examine it from a variety of directions, so that you will have a more complete understanding from which to make a decision. Knowledge is power. The best approach would be to simply experiment for yourself, as the only thing that really matters – after all is said and done – is how YOU personally feel."

"As I stated at the beginning of this article, the issue of sodium is a bit complex. I have tried to examine it from a variety of directions, so that you will have a more complete understanding from which to make a decision. Knowledge is power. The best approach would be to simply experiment for yourself, as the only thing that really matters – after all is said and done – is how YOU personally feel."

Sodium, Nutritional Ketosis, and Adrenal Function - Phinney and Volek

In which Stephen Phinney, MD, PhD Jeff Volek, PhD, RD show how supplementing salt in a ketogenic diet will alleviate some of the symptoms of 'keto flu'.

In which Stephen Phinney, MD, PhD Jeff Volek, PhD, RD show how supplementing salt in a ketogenic diet will alleviate some of the symptoms of 'keto flu'.

1 gram of sodium is 2.5 grams of salt

1 teaspoon of salt is 5 grams (equivalent to 2 grams of sodium)

1 teaspoon of salt is 5 grams (equivalent to 2 grams of sodium)

What about some added salt? Here is an expert on salt in the diet and what happens to it... Summary

Sodium is an essential nutrient involved in fluid and electrolyte balance and is required at a very closely controlled extracellular concentration of 137-145 mmol/L for normal cellular function [1].

The main function of sodium in the body is to maintain the transmembrane electrical potential with sodium on the outside of the (cell) membrane and potassium on the inside. This is crucial for the survival of all cells. [2]

Salt is excreted totally passively by the glomeruli when the blood is filtrated in the kidneys. The excretion capacity is practically unlimited with 1 000 grams to 2 000 grams of salt per day [3].

The major problem for the body and the kidneys is to reabsorb enough sodium (usually more than 99 % but less than 100 % of excreted sodium in glomeruli) from the primary urine to stabilize and maintain the normal level of sodium in blood and extracellular fluid at the precise level of 137-145 mmol/L [4].

We are therefore unable to manipulate the blood pressure by manipulating the amount of sodium in the food. All excess of sodium intake is immediately excreted in the renal glomeruli and not reabsorbed in the renal tubuli. Any deficiency in sodium intake versus sodium excretion is almost immediately life threatening. It is totally safe to let us be guided by our gustatory system when we add salt and water to our food. We do have multiple sodium sensors and volume sensors in our body including a central processing unit closely controlling both sodium and water levels in the body.

There is no scientific relationship between salt intake and blood pressure/hypertension. There is no way to manipulate the blood pressure by manipulating the salt intake.

More on the subject:

Sodium is an essential nutrient involved in fluid and electrolyte balance and is required at a very closely controlled extracellular concentration of 137-145 mmol/L for normal cellular function [1].

The main function of sodium in the body is to maintain the transmembrane electrical potential with sodium on the outside of the (cell) membrane and potassium on the inside. This is crucial for the survival of all cells. [2]

Salt is excreted totally passively by the glomeruli when the blood is filtrated in the kidneys. The excretion capacity is practically unlimited with 1 000 grams to 2 000 grams of salt per day [3].

The major problem for the body and the kidneys is to reabsorb enough sodium (usually more than 99 % but less than 100 % of excreted sodium in glomeruli) from the primary urine to stabilize and maintain the normal level of sodium in blood and extracellular fluid at the precise level of 137-145 mmol/L [4].

We are therefore unable to manipulate the blood pressure by manipulating the amount of sodium in the food. All excess of sodium intake is immediately excreted in the renal glomeruli and not reabsorbed in the renal tubuli. Any deficiency in sodium intake versus sodium excretion is almost immediately life threatening. It is totally safe to let us be guided by our gustatory system when we add salt and water to our food. We do have multiple sodium sensors and volume sensors in our body including a central processing unit closely controlling both sodium and water levels in the body.

There is no scientific relationship between salt intake and blood pressure/hypertension. There is no way to manipulate the blood pressure by manipulating the salt intake.

More on the subject:

- Another article on dangers of reducing salt in the diet.

"The committee found no evidence for benefit and some evidence suggesting risk of adverse health outcomes associated with sodium intake levels in ranges approximately 1,500 to 2,300 mg/day among those with diabetes, kidney disease, or CVD. Further, the evidence on both the benefit and harm is not strong enough to indicate that these subgroups should be treated differently than the general U.S. population."

"The average American takes in 3,400 mg of salt a day, about 1½ teaspoons. The federal guidelines say that it should be brought down to less than 2,300 mg a day. It’s a good thing that people have not been following their doctors’ advice, because it would have been killing them." - No Benefit Seen in Sharp Limits on Salt in Diet

- Fatal and Nonfatal Outcomes, Incidence of Hypertension, and Blood Pressure Changes in Relation to Urinary Sodium Excretion

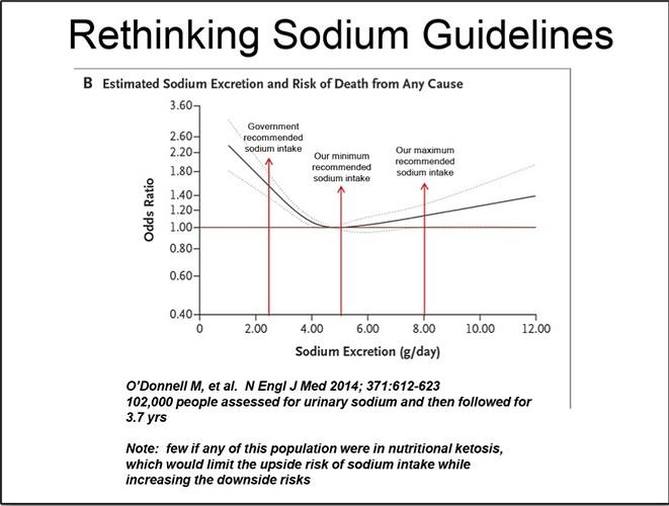

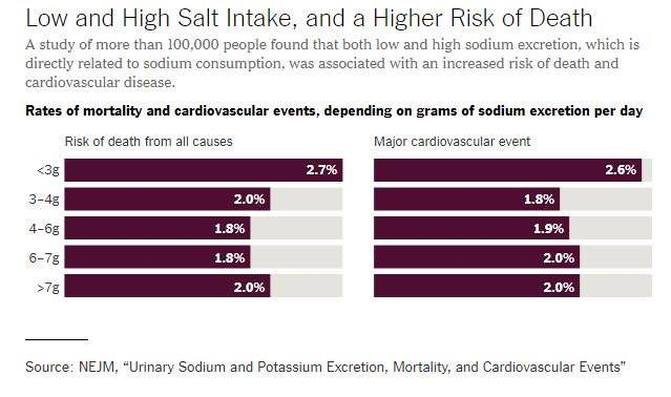

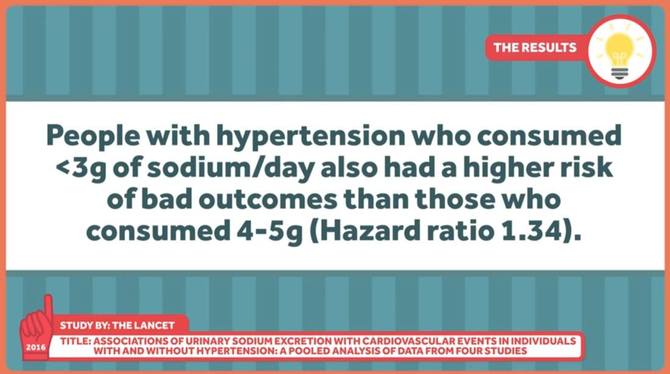

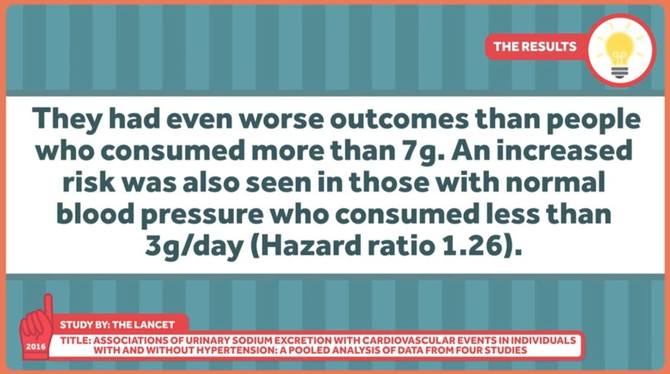

In this study in which sodium intake was estimated on the basis of measured urinary excretion, an estimated sodium intake between 3 g per day and 6 g per day was associated with a lower risk of death and cardiovascular events than was either a higher or lower estimated level of intake. As compared with an estimated potassium excretion that was less than 1.50 g per day, higher potassium excretion was associated with a lower risk of death and cardiovascular events. - Relationship Between Nutrition and Blood Pressure: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the NutriNet-Santé Study, a French Web-based Cohort Study

- Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Events

(The one with the 'j' curves relating to salt excretion and mortality) - What Vilhjalmur Stefannson wrote about salt

- Low Salt Diet Increases Insulin Resistance in Healthy Subjects

- Pink Himalayan Sea Salt: An Update

Pink Himalayan sea salt is advertised to contain “the 84 trace minerals valuable to the body.” Naïve customers assume that more is better, and that we need more trace nutrients, so those 84 minerals ought to make pink Himalayan salt healthier than regular salt. That assumption is completely misguided. - A leading cardiovascular research scientist weighs in on the debate

So next time you feel a craving for salt, do yourself a favour and give in to it. Your body says these things for a reason. - Eating less salt may be making you gain weight

- Low-sodium diet might not lower blood pressure - 2017

Findings from large, 16-year study contradict sodium limits in Dietary Guidelines for Americans - Pass the salt: Study finds average consumption safe for heart health: PURE study - 2018

- Scant Evidence Behind the Advice About Salt - NY Times Article - 2018

- The technical report on sodium intake and cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries by the joint working group of the World Heart Federation, the European Society of Hypertension and the European Public Health Association

"Therefore, there is consistent evidence from clinical trials and observational studies to support reducing sodium intake to less than 5 g/day in populations, but inconsistent evidence for further reductions below a moderate intake range (3-5 g/day)." - The wrong white crystals: not salt but sugar as aetiological in hypertension and cardiometabolic disease

Thus, while there is no argument that recommendations to reduce consumption of processed foods are highly appropriate and advisable, the arguments in this review are that the benefits of such recommendations might have less to do with sodium—minimally related to blood pressure and perhaps even inversely related to cardiovascular risk—and more to do with highly-refined carbohydrates. It is time for guideline committees to shift focus away from salt and focus greater attention to the likely more-consequential food additive: sugar.

Modern Scientific Controversies Part 1: The Salt Wars

Kip Hansen / June 9, 2016

What We Know About Dietary Salt:

What We Know About Salt Politics:

Kip Hansen / June 9, 2016

What We Know About Dietary Salt:

- Salt is an absolutely necessary element of the human diet – humans die without adequate salt intake.

- For most people, consuming a moderate amount of salt daily (2,500-5000 mgs) has no adverse effects.

- High blood pressure (BP) is associated with cardiovascular disease and risk of premature death.

- For almost everyone, eating more salt causes an increase in BP, but the increase is not clinically important, averaging around 2.1/1.1 mmHg.

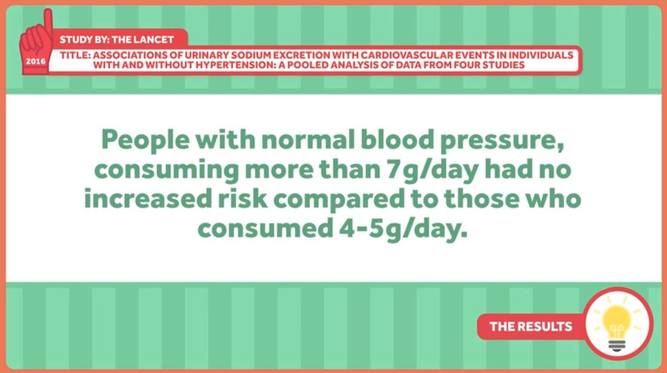

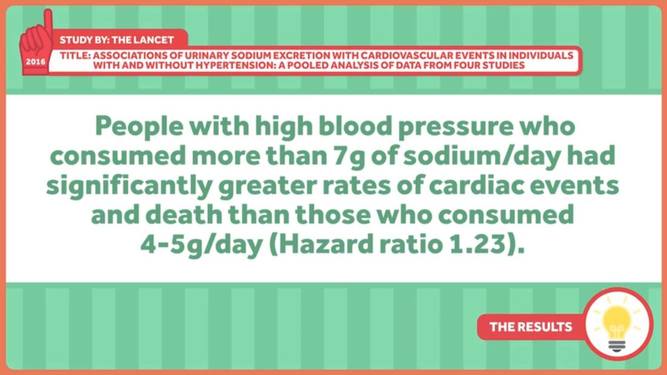

- For a certain percentage of people, believed to be in the 10-15% range, who can be labeled “salt sensitive”, dietary salt causes higher BP and for those already suffering high BP and who have a high salt intake, dietary salt reduction combined with improved diet (the DASH diet – more fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy, specifically) can help reduce BP to healthier levels.

- For most people, a diet too low in salt increases risk of cardiovascular events and increase risk of all-cause death.

- The science to quantify what constitutes “too low”, “moderate”, and “too high” regarding salt intake is best characterized as “somewhat uncertain”.

What We Know About Salt Politics:

- The Salt Wars have been raging for 30 years, at least.

- One side of the Salt Wars believes that because dietary salt increases BP (in most people just by a small amount) and causes a big increase BP in some people, coupled to the idea that high BP is associated with increased heart disease and risk of death, that governments should take action to reduce the salt intake of everyone – population wide – through regulation of the food industry, setting dietary guidelines, etc. Arrayed on this side we find the American Heart Association, United Nations’ World Health Organization, and the US FDA. Many food and diet advocacy groups stand with the AHA against salt. Taken together, these groups represent a view that consists of a “bureaucratically entrenched hypothesis advocating an enforced solution”.

- The opposition believes that the science is not adequate to mandate a population-wide reduction of salt intake, maintaining that, in addition to being not necessary, it will cause harm instead of good, increasing cardiovascular events and premature death among all groups. The majority of scientists on this side of the issue also hold that the DASH diet is far more effective in reducing high BP than salt reduction.

- Despite the mounting evidence of harm from population-wide enforced salt reduction, various government agencies have been passing rules, regulations, and guidelines to force the food processing industry and, most recently, in New York City, mandatory labeling of highly salted foods by chain restaurants.

- As in all modern scientific controversies, the faction occupying a societal Bully Pulpit, in this case the AHA, FDA, and WHO, has a huge advantage, even when the hard scientific facts are not on their side. [“A bully pulpit is a sufficiently conspicuous position that provides an opportunity to speak out and be listened to…. a terrific platform from which to advocate an agenda.”]

- The Salt Wars are an exemplar of what can happen when a hypothesis is scientifically correct but its real-world overall effect becomes grossly exaggerated. This can lead to a “mandated solution” which is then sold as a cure-all for some existing problem. As the underlying science is in fact uncertain, scientists in support of this view must turn themselves into advocates to make their case. Political advocates in turn pretend to be scientists, advising governments to enforce a “one-size-fits-all” solution on the whole society – even though it is probable that the claims of benefit range from uncertain, at best, to nonsensical [see footnote 2 for the my rationalization for this statement in the Salt Wars].

Salt in New Zealand

Captain James Cook saw Polynesians in Hawaii manufacturing salt in the late 1700s, but it was never produced by Māori in New Zealand. Nevertheless, Māori had a conception of saltiness in their word mātaitai, meaning tasting of salt, or brackish. Their sodium needs were met through a diet of fish and shellfish. When salt was introduced by Europeans, some Māori believed that eating salted foods caused their people to contract illnesses previously unknown to them. However, the real reason was that Māori had no natural immunity to the infectious diseases introduced by Europeans. |

Here is the actual story of salt-making in New Zealand. https://teara.govt.nz/en/salt

|

Iodine in Salt

Does iodine added to salt lose effectiveness over time? Yes it can, but this depends on where the salt comes from and how much moisture can get to it as well as how refined it is. Here is the study.

Does iodine added to salt lose effectiveness over time? Yes it can, but this depends on where the salt comes from and how much moisture can get to it as well as how refined it is. Here is the study.

Higher dietary salt intakes reduce gout triggers: Study

19-Aug-2016 By Will Chu

A high-salt diet has been found to lower blood levels of uric acid, a recognised trigger of gout, according to a study by US researchers.

Link to study

19-Aug-2016 By Will Chu

A high-salt diet has been found to lower blood levels of uric acid, a recognised trigger of gout, according to a study by US researchers.

Link to study

Sodium restriction and insulin resistance: A review of 23 clinical trials

We discovered 23 human clinical studies showing that low-salt diets worsen markers of insulin and glucose. Caution is advised when recommending salt restriction for blood pressure control as this may lead to worsening insulin resistance.

We discovered 23 human clinical studies showing that low-salt diets worsen markers of insulin and glucose. Caution is advised when recommending salt restriction for blood pressure control as this may lead to worsening insulin resistance.

| low-salt-insulin-resistance.pdf | |

| File Size: | 681 kb |

| File Type: | |

Ted Talk About Water Excretion, Urea Creation and Muscle Waste on a High Salt Diet

Jens Titze

Jens Titze